The 170-year-old beer found off the coast of Finland, buried in a shipwreck at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, shines new light on beer-crafting processes of long ago. Though the smell of this mid-18th-century brew was rancid (no smell compared to burnt rubber and goats ever is good), researchers were able to determine that the original taste might not have been too far off from our modern-day ales.

Fancy that.

Anyone with an interest in the craft brew scene probably knows their fair share about the techniques employed to get the beer into their glass. However, a much smaller percentage knows much about the techniques used in brewing beer from centuries past. Was it all that different? (Spoiler alert: yes it was.) When was beer even invented? The answer may surprise you.

The discovery of some of the world’s first-known libations comes at the hands of Dr. Patrick McGovern, the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia. (He’s also an Adjunct Professor of Anthropology—busy guy!)

Called the “Indiana Jones of Ancient Ales, Wines and Extreme Beverages,” Dr. Pat, as he’s known to colleagues and brew masters, has sniffed out some of the world’s oldest booze, including the world’s oldest barley beer (from Iran’s Zagros Mountains, 3400 B.C.), the oldest grape wine (Zagros Mountains, 5400 B.C.) and an unbelievably ancient grog from China’s Yellow River Valley crafted almost 9,000 years ago.

Though not confirmed, his discovery of starch-dusted stones at the ancient Wadi Kubbaniya, an 18,000-year-old site in Upper Egypt, suggests ancient Egyptians were making beer even then!

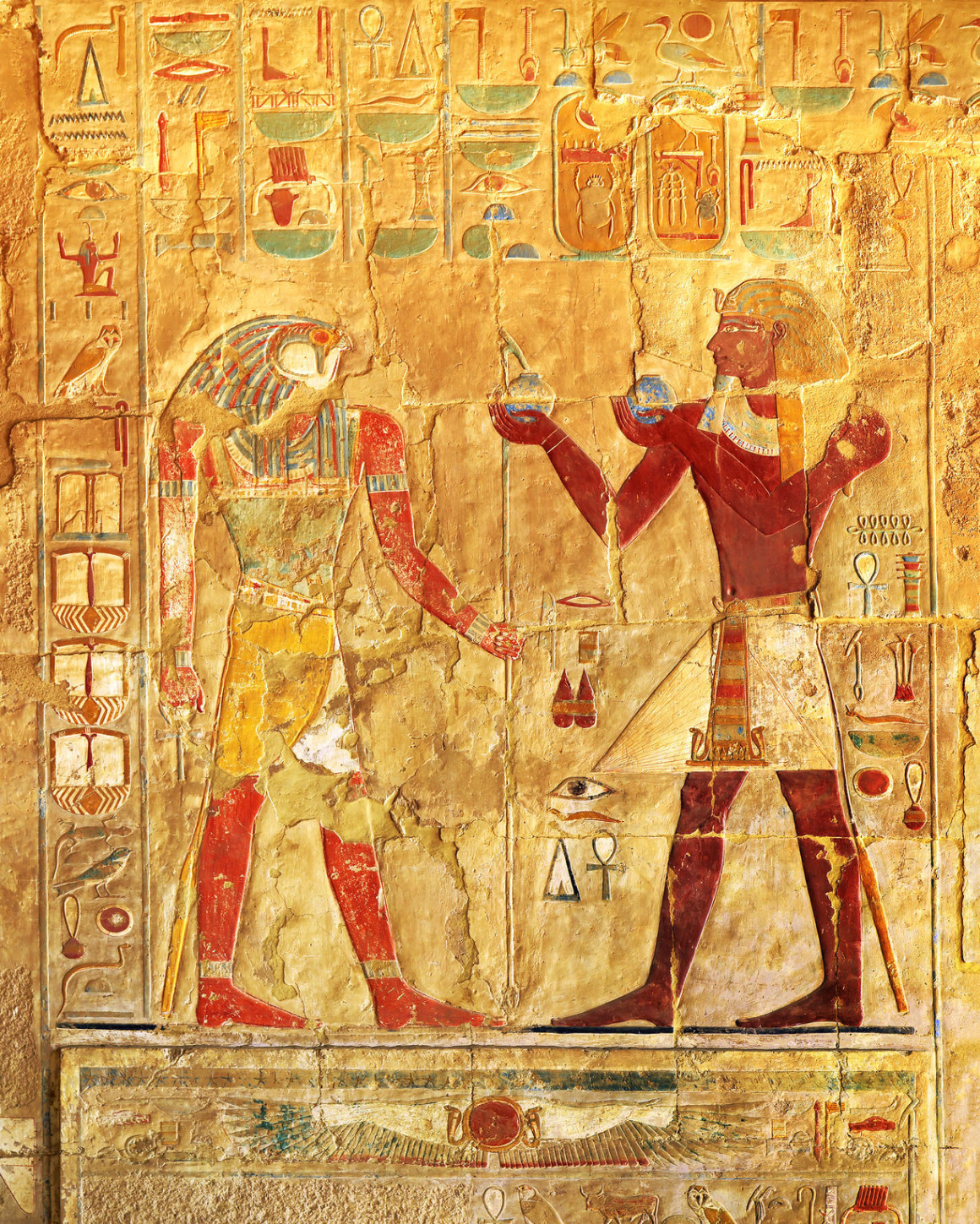

These discoveries have opened the door to ancient beer recipes and rituals spanning the globe. Let’s start with the Egyptians, whose improvised blood-red beers took a unique approach with the (unbeknownst to them) absence of hops.

The process started in a bakery, where brewers would winnow and thresh the grain and filter it through sieves made of rushes. Then they would grind the grain down and form the flour into bread dough, which would then form soggy loaves shaped like bells, called cyllestis. When the loaves were ready, they were moved from the oven and each loaf was divided into quarters and drenched in water—the equivalent of today’s malting process.

Ancient Egyptians flavored their “mash” with dates, honey, olive oil, bog myrtle, cheese, meadowsweet, mugwort, carrot, herbs and other spices. (They also were known to throw in hallucinogens such as poppy or hemp.) After fermentation, the mush was transferred into casks and further softened by stomping or grinding. Additional water was added, and finally the mash was strained and rinsed with “sparge” water. The collected run-off began to rest in crocks and hardened. The finished beer was placed in new crocks, which were sealed and kept in cellars, or even buried, before consumption.

At a 2,550-year-old excavated Celtic site found in southwestern Germany, a another process was uncovered.

Archaeologists speculate that barley was soaked in specially built ditches until it sprouted. The grains were dried by fires lit on either end of the ditches, which imbued the concoction with a smoky taste and darkened its color. The slow drying process stimulated lactic acid bacteria, a technique still used today.

The medieval Celts most likely used mugwort, carrot seeds or henbane to flavor their ale, as was custom at the time (henbane would have increased the beer’s alcohol content). The fermentation likely occurred by placing heated stones in the liquefied malt and using yeast-coated brewing apparatus, or by adding fruit or honey (which contain wild yeasts).

The end result would have been a cloudy beer, containing yeasty sediments, best enjoyed at room temperature. Not your typical brew by today’s standards. In a 1,600-year-old poem from Roman emperor Julian, Celtic beer is described as smelling “like a billy goat.” Perhaps not too far off from the beer found in the Baltic Sea.

Not only has Dr. Pat’s findings helped to solidify the history of beer, he has helped to introduce its flavors to modern times. Since 1999, Dr. Pat has worked closely with Dogfish Head Brewery in creating Ancient Ales, beers paying homage to civilizations of millennia past.

This line includes Midas Touch, crafted based on molecular evidence found in a Turkish tomb believed to belong to King Midas; Chateau Jiahu, inspired by an ingredient list from a 9,000-year-old Chinese tomb; Theobroma, derived from chemical analysis of 3,400-year-old pottery pieces found in Honduras; and many more.

Turns out, you can teach a new brewmeister old (or should we say ancient?) tricks.