As anyone who’s drained more than one tulip glass of the concoction can tell you, no two saisons are alike. Some open with a peppery bite, some broaden into an herbal finish, some smack of a cider-like sourness, while others are just downright funky. How, then, can we even begin to talk about saison as a distinctive style?

The answer hinges on deepening our understanding of history and gaining an appreciation of beer’s significance in a larger cultural context.

History of saison

Saisons originated in a region of Belgium known as Wallonia. Wallonia is located in southern Belgium and is populated by French-speaking (rather than Flemish-speaking) peoples. Bordering tiny Luxembourg and the western reaches of Germany (Düsseldorf, home of top-fermented altbier; Cologne, the city that gave us the classic lager Kölsch), Wallonia is also home to three Trappist monk communities — Chimay, Orval and Rochefort — renowned the world over for their ales. In short, Wallonia is a region with a very particular culture that also happens to be situated in the heart of Europe’s breadbasket and at the intersection of several different continental brewing traditions. And, as we will see, locality matters a great deal in making a saison a saison.

Saisons originated in a region of Belgium known as Wallonia, located in southern Belgium and populated by French-speaking peoples. Wallonia is home to a very rich brewing culture.

And what about that name? Saison is simply French for “season.” Saison is technically a winter beer, albeit one prepared for summer consumption. Saisons date back to an age before refrigeration. In addition to keeping the beer from spoiling, winter brewing also gave the managers of Wallonia’s large farming estates something to keep their field hands busy in between the fall harvest and spring planting seasons. For this reason, you might find saisons or saison-style beers referred to as farmhouse ales.

A beer for the working man

These ales can be as or even more complex than their Trappist cousins, yet, for much of their history, saisons have been working class. Potable water was not something any community could take for granted in Medieval Europe. Beer was essential to everyday human hydration. In fact, saisons were customarily included in every farm worker’s “beer allotment.” According to Phil Markowski, author of The Oxford Companion to Beer, each worker could consume up to five liters (approximately 1 1/3 gallons) of saison per day during the hottest months of the year, when hours spent tilling crops were at their longest and most back-breaking. And some of these workers were truly seasonal employees: saisonniers. Some beer styles are named after their ingredient lists or flavor profiles; some after the region that first made them famous; some in recognition of their inventors. Saison may be one of the rare beers named after those essentially anonymous individuals who most frequently consumed it.

So, what is a saison?

Enough anthropology; to plumb the depths of the enigma that is saison, we need a chemistry lesson. Almost more than any other style of ale, saison is all about the yeast. Saisons are fundamentally local, even hyperlocal, products. Like wine, saison is a culinary representation of the soil, the atmospheric conditions and the microbial ecology of the discrete places in which it is produced.

Traditionally, saisons are spontaneously fermented. In other words, whatever undomesticated yeast just happens to be “floating around” is allowed to snack on the wort, transforming that porridge-like substance into beer and converting sugars into carbon dioxide, alcohol and two acidic compounds chiefly responsible for the saison’s singular notes: esters and phenols. While most commercial brewers carefully cultivate certain strains of yeast in order to produce specific styles of beer, saison makers surrender a good bit of control over the final product. Modern saisons are most often brewed using carefully bred alternatives to Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ale yeast) and Saccharomyces uvarum (lager yeast). A serious saison brewer will probably make some note of the yeast varietals, some of them proprietary, in their promotional literature or on the bottle itself.

image credit: Bell’s Beer

And there’s more to the bottling of a saison than attaching an eye-catching label. Saisons are traditionally bottle conditioned. On bottling, dollops of extra yeast and/or sugar are added, bringing the beer “back to life.” If most beers are analogous to (and pair well with) cheese, saison is more like yogurt: a delicious shelter for active cultures.

Somewhat counter-intuitively, the second fermentation consequent from bottle conditioning does not produce a high-alcohol beer. An authentic saison should sport an ABV no higher than 7.5% or 8%. What bottle conditioning does accomplish, however, greatly affects of the dynamics of the saison’s savor and the character of its sparkle. Bottle-conditioned beers need not have extra CO2 injected for fizz; their carbonation levels, while strong, bubble rather gently.

What makes a good saison?

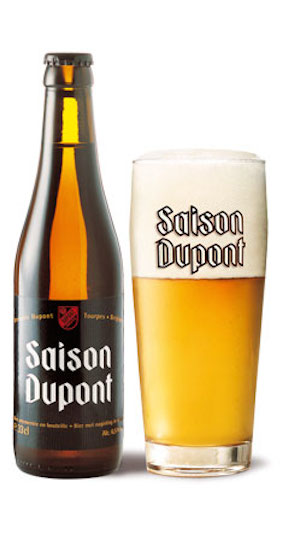

A good saison, like any improvisation, is the unique outcome of a set of rules that nevertheless accommodate a certain amount of free play and elements of chance. And a good number of the most popular saisons — Saison Dupont, Brooklyn’s Sorachi Ace, Tank 7 from Kansas City, MO’s Boulevard Brewing Co. — are available year-round. And the style, with all its challenges, is one that craft breweries are increasingly adding to their rosters.

image credit: Brasserie Dupont

But what should any beer-lover, seasoned or not, look for in a good saison? A golden, almost orangish hue characterized by mild cloudiness (evidence of bottle conditioning, as that “extra” yeast has not been filtered out) is always a good sign. Ditto a fairly generous and stable head. A good saison should be luscious and slightly bready but also thirst-quenching. Saisons should be tart (not syrupy), but quite modest in terms of their bitterness. But most important of all: The saison should be rich and even surprising in its flavor profile, and it should come out of the bottle with a rustic, citrus-saturated aromatic flourish.

Do you have a favorite saison, whether it’s one to set by the cheese board or ideal for downing after a broiling afternoon behind the lawnmower? Is there a brewer or brewery in your neck of the woods getting ready to let its own experimental ale out of the farmhouse? What’s your own experience with aging beers? Knurd-out with us in the comments below and at your local Flying Saucer.